History of the Port Sanilac Lighthouse

Bark Shanty in the 1840s

Originally established as a lumberjack settlement named Bark Shanty in the 1840’s, the village was established and renamed Port Sanilac in 1857 when shipping docks were built into the lake.

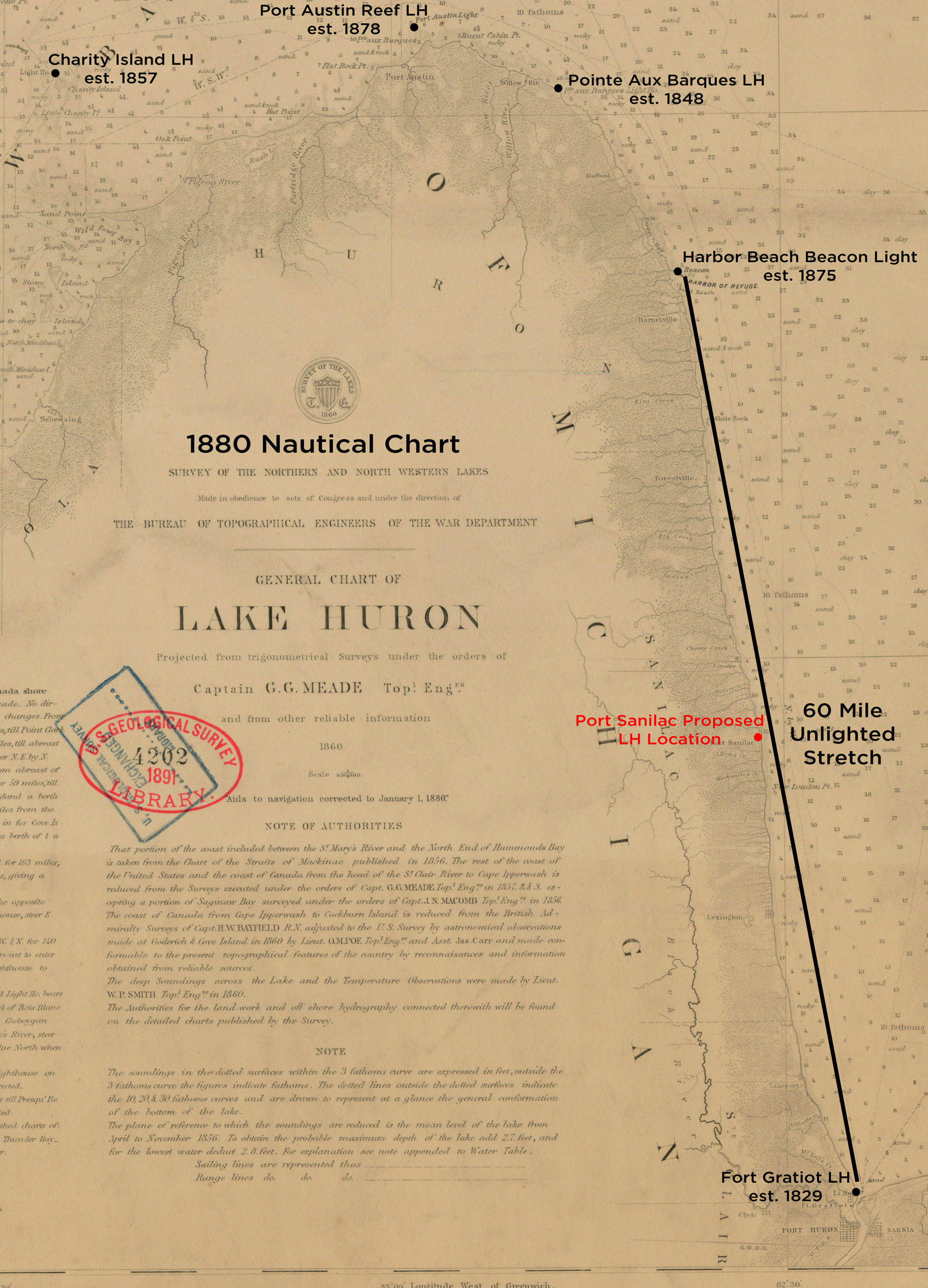

With the opening of navigation into Lake Superior through the Sault Lock in 1853, and an increasing number of vessels being launched to service the increasing commerce, the number of vessels coasting Lake Huron's southwestern shore increased dramatically throughout the 1860's. While the 1825 Fort Gratiot Light served to mark the entrance to the St. Clair River at the foot of the lake, and the 1848 Pointe Aux Barques Light guided vessels around the tip of Michigan's "Thumb," the intervening 75-mile stretch remained unlighted, with vessel masters running blind along a forty-mile stretch of coastline beyond the range of visibility of either of the two Lights.

Congress Report in 1868

With pressure from maritime interests, the Lighthouse Board first broached the need for a Coast Light along this stretch in its 1868 annual report to Congress, requesting an appropriation of $30,000 to cover the cost of establishing the station at an as yet undetermined location. While the Board reiterated the request in each of its four subsequent annual reports, Congress appears to have been unconvinced of the need for the station, as no appropriation was forthcoming. However, convinced of the need for the Light, the Board continued to push for funding, even increasing the amount of the requested appropriation to $40,000 in its 1873 annual report.

While the establishment of the Sand Beach Harbor of Refuge Light in 1875 reduced the length of unlighted coastline by approximately sixteen miles, 30 miles of dangerous coastline remained unlighted, and the Board continued to push for the funds on an annual basis. Congress finally responded to the Board's seemingly incessant pleas in 1885. However, they were evidently wary of the requested costs, as the amount of the appropriation was arbitrarily reduced to $20,000, a mere half the amount requested.

Selecting Port Sanilac

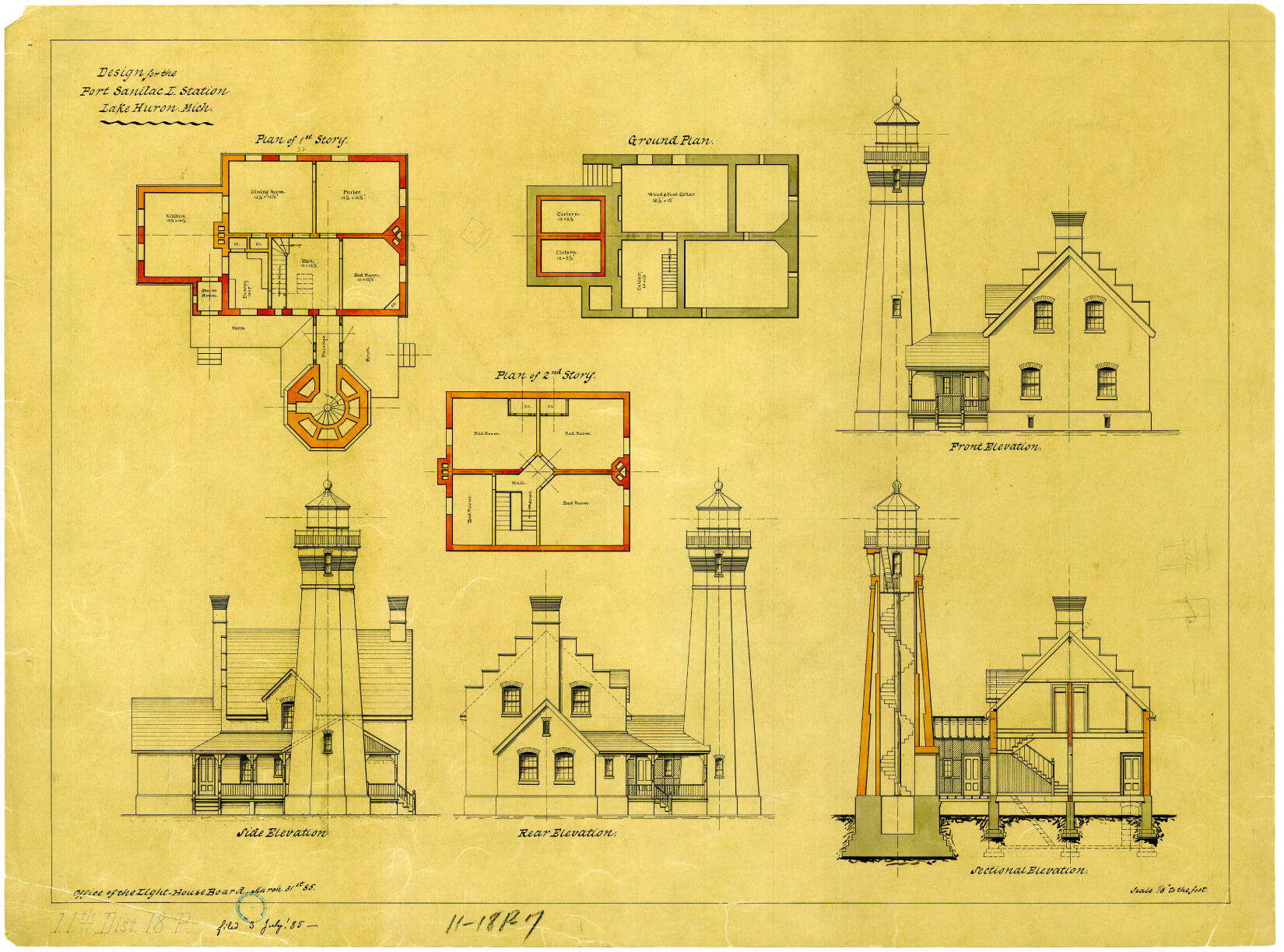

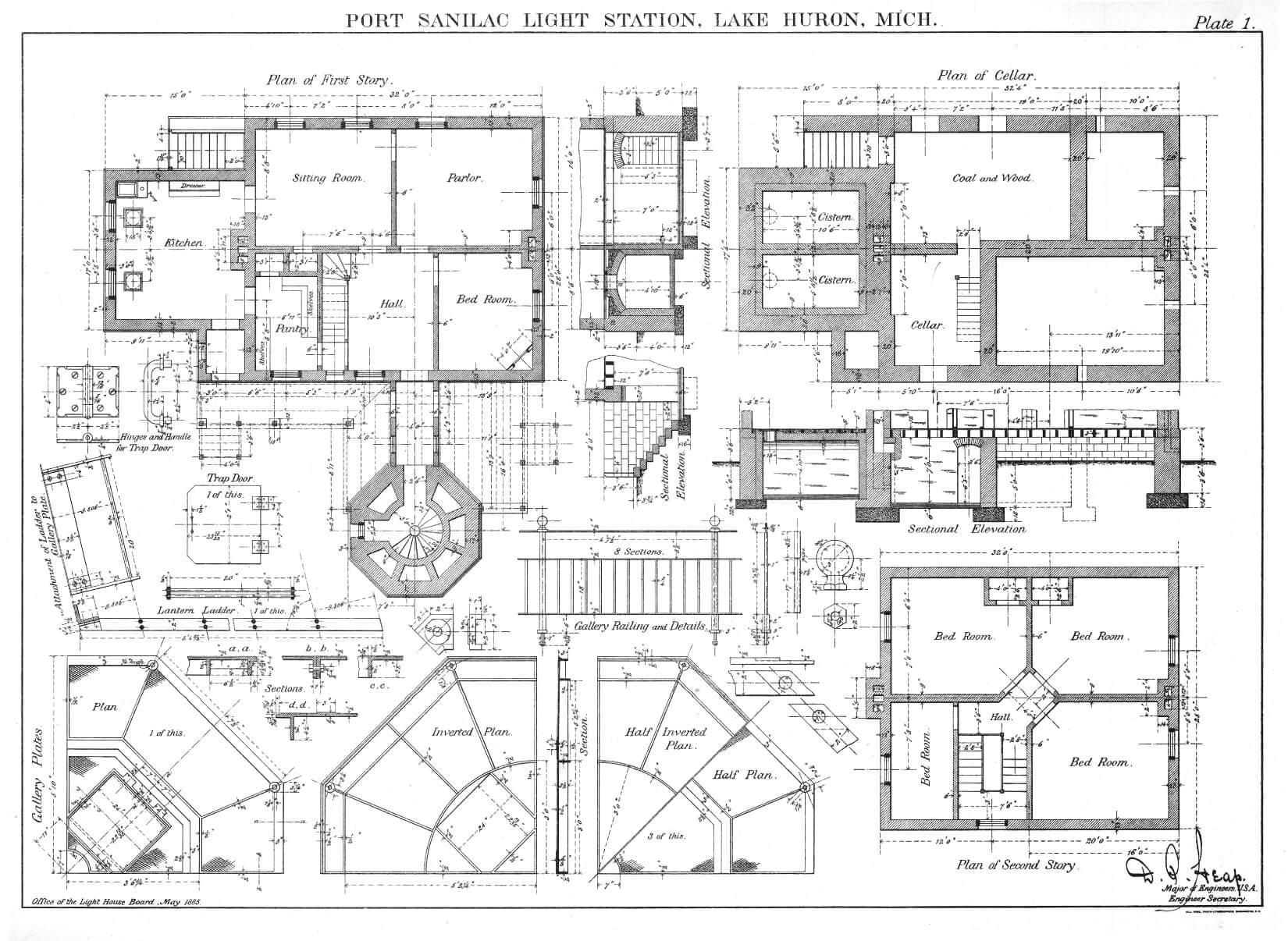

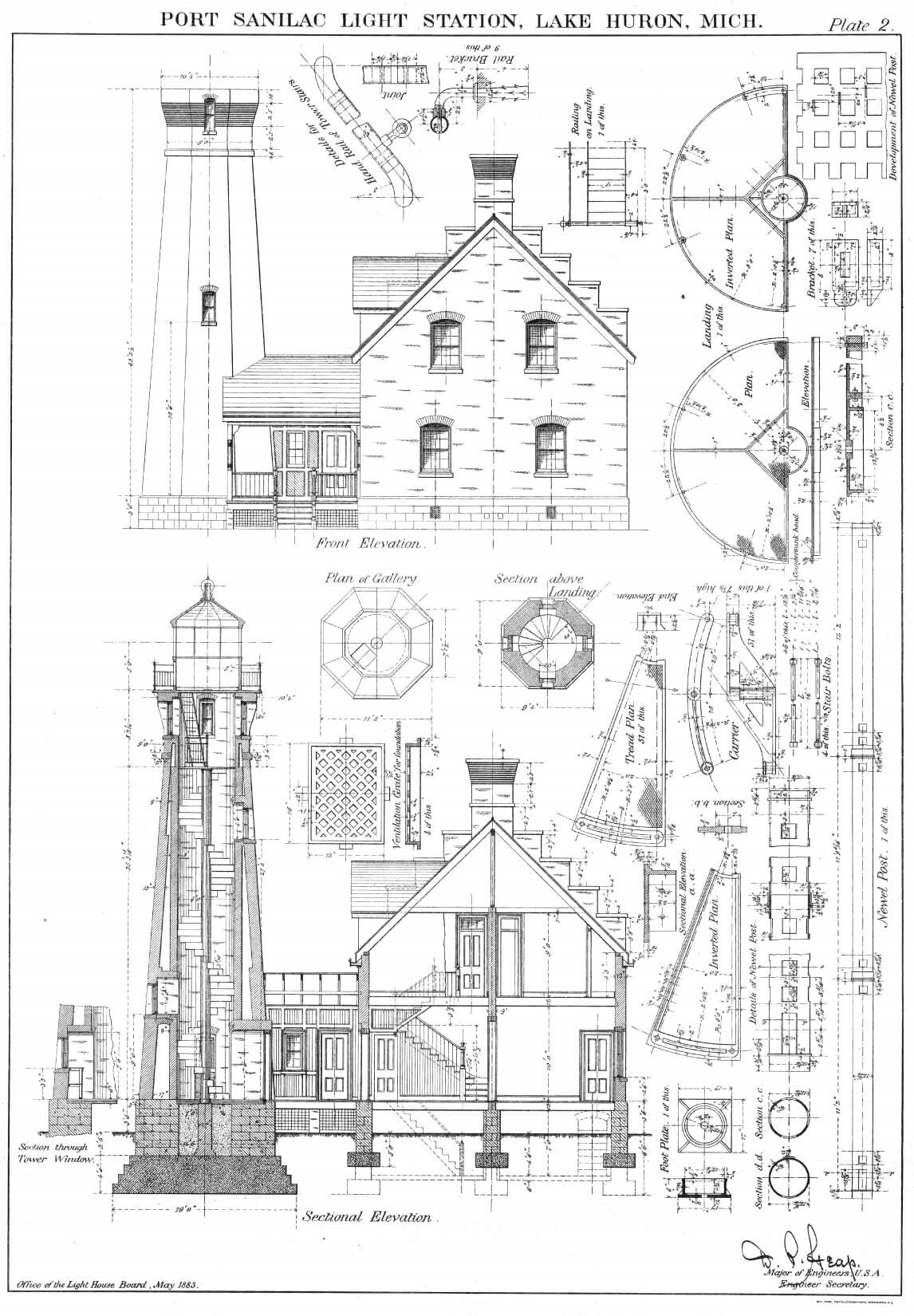

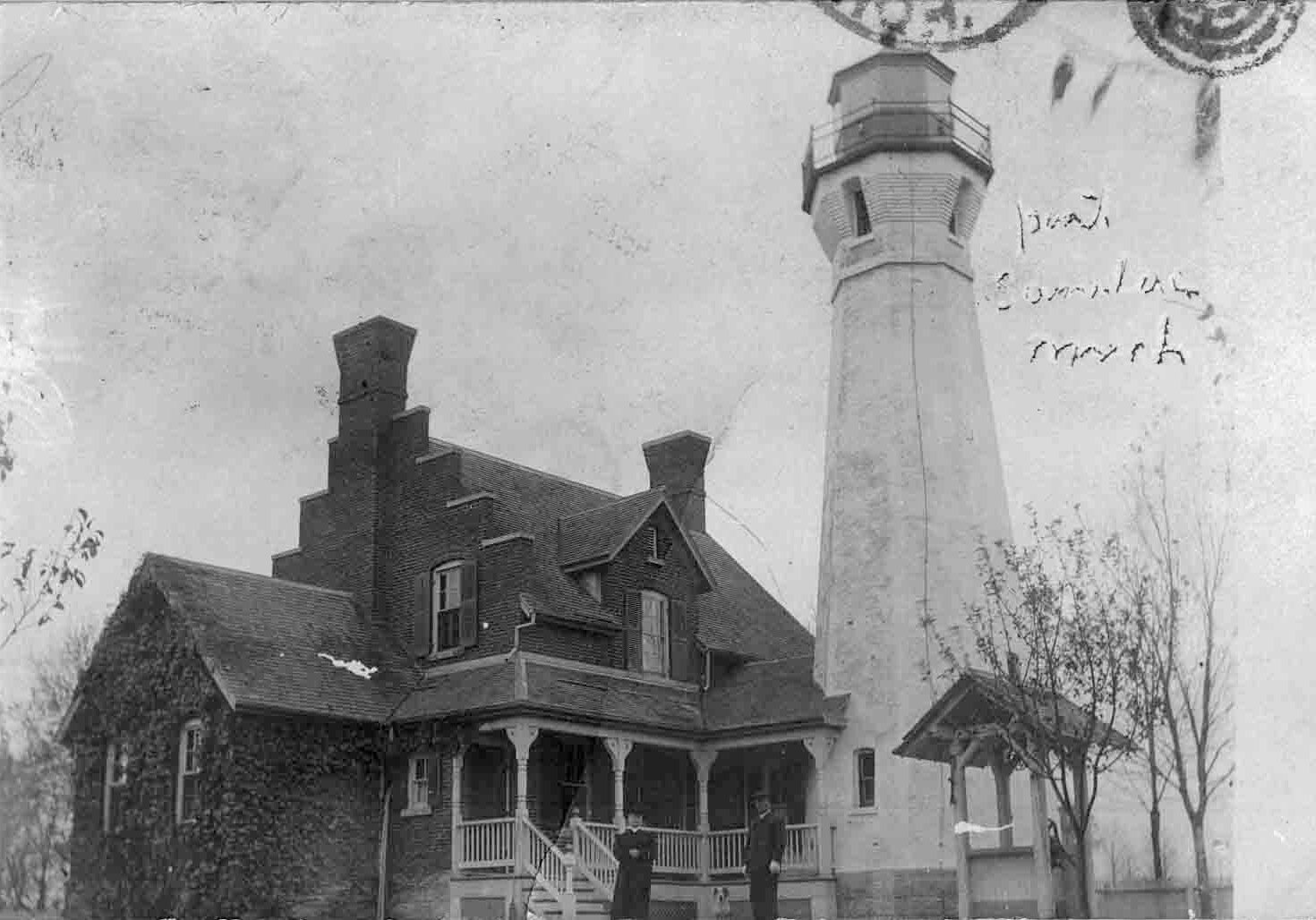

Selecting Port Sanilac as the optimal location for the new station, a site selected on high ground at the head of the small bay. With steps underway for obtaining title to the chosen site, Eleventh District Engineer Captain Charles E. L. B. Davis set about creating plans and specifications for construction of the new station. Amazingly, Davis' plans called not only for a station which could be built within the tight limitations of the budget, but also managed to create a design that was both unique and architecturally significant in its elegance.

Contracts specifying a completion date of October 15, 1886 were awarded for materials and construction, and the iron work for the lantern and stairs delivered at the Detroit lighthouse depot on October 1, 1885. The construction crew arrived at Port Sanilac on June 7, 1886, and with only four and a half months remaining to complete the project, work at the site began at a feverish pace. By the end of June, it was reported that the cellar had been excavated, the dwelling walls were almost half raised, the timber and stone foundation for the tower installed, and all construction materials had been delivered to the site.

Help Save Lighthouses – Donate Now

Help support the Michigan Lighthouse Conservancy with your thoughtful donation

Captain Davis' Design

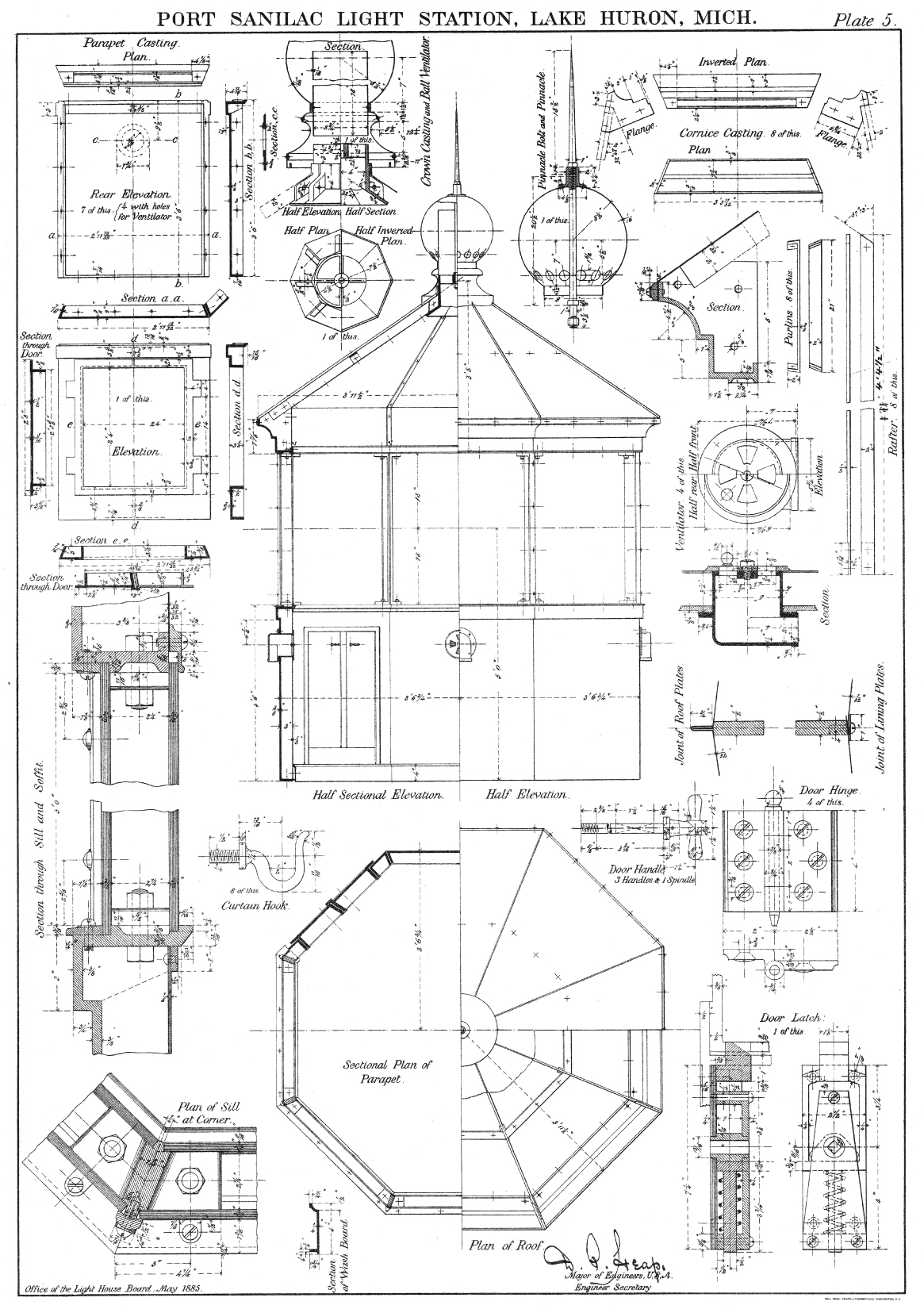

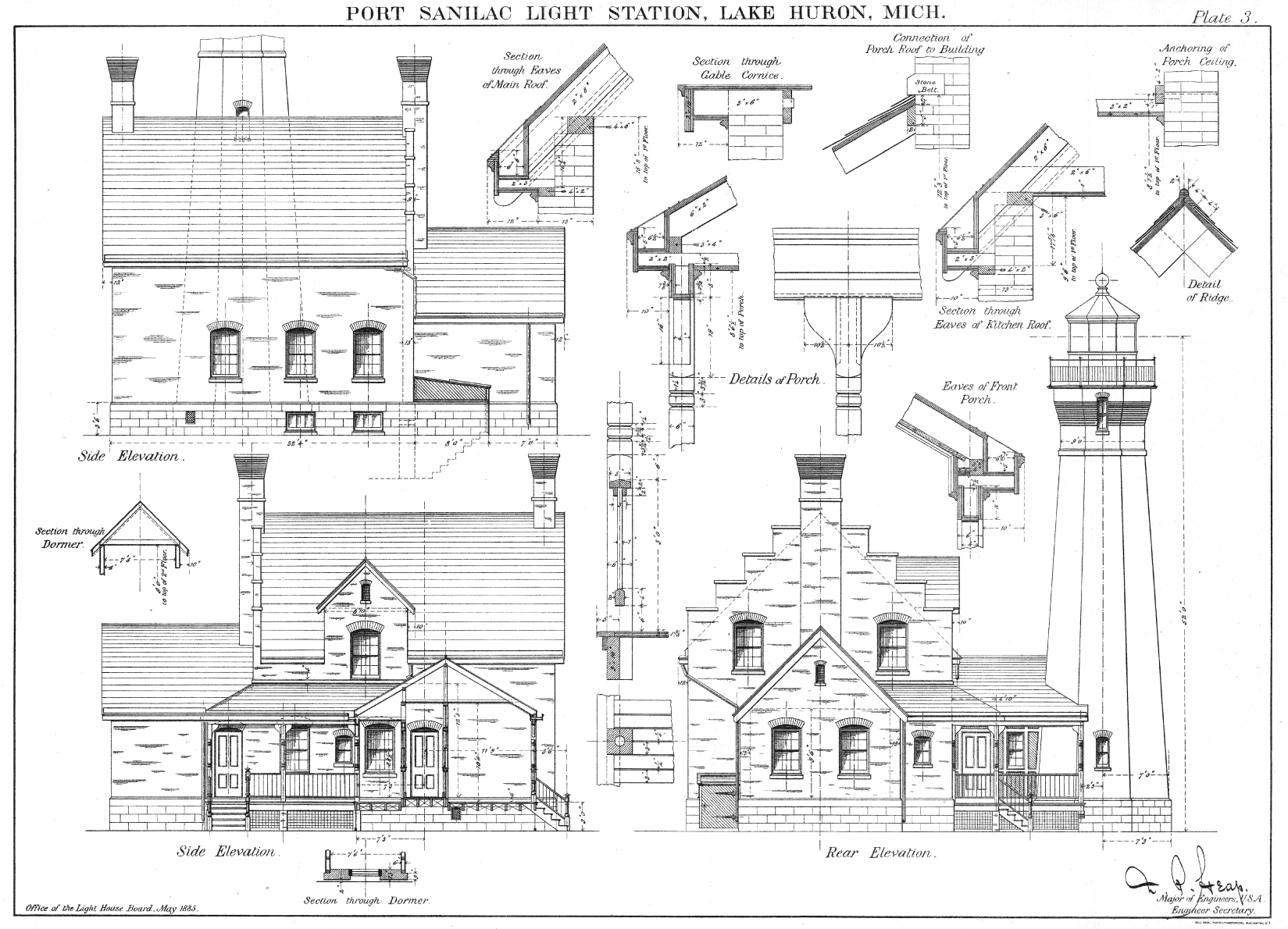

Captain Davis' design called for an octagonal brick tower standing 14 feet in diameter at the base, gracefully tapering vertically to a diameter of 9 feet below the gallery. Instead of supporting the gallery with a series of corbels as was the custom, twelve successive courses of bricks were laid so as to stand proud of the course immediately below, creating a flared "stair-stepped" support for the gallery.

Four windows were let into the flared area to create a watch room from which all quadrants of the horizon could be observed. Atop the gallery, a prefabricated octagonal cast iron lantern was erected, and outfitted with a fixed white Fourth Order Fresnel lens manufactured by Barbier and Fenestre of Paris. The octagonal brick tower has a focal plane of 52 feet, with a total tower height of 59 feet. The light sits 69 feet above the lake level on the bluff.

Equipped with double reflecting prisms in the rear of the lens, the lens was installed in such a way that the double reflecting prisms blocked the lens on the landward side, redirecting the light out in a 300 degree arc across the water. Seated at a focal plane of 69 feet, it was calculated that the light would be visible for a distance of 13 miles at sea.

Building Port Sanilac

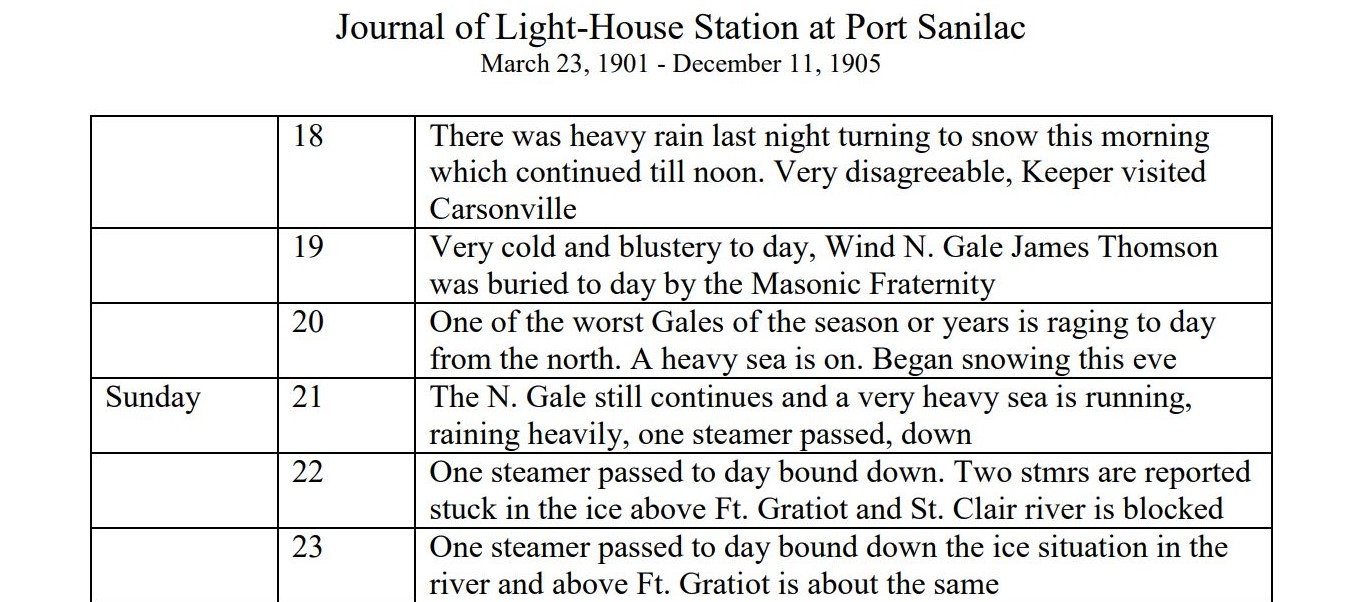

Port Sanilac Historic Log Books

Beginning in 1872, the Federal Government started requiring lighthouse keepers to keep Log Books. The US Light House Service became part of the US Coast Guard in 1939. Lighthouse keepers and assistant keepers maintained these logbooks as a full record of station activities, written up at the end of each watch. At the end of each watch, the keeper or assistant keeper transcribed in the logbook a narrative description of events occurring during the watch concerning aids to navigation, accidents, drills and exercises, ceremonies, official visits, inspections, navigational details, personnel, and special operations. The log book provide access to an insight into the daily duties of the light keeper.

The lighthouse log books for Port Sanilac that have been transcribed can be accessed here via this link along with a digital index of topics accessed here via this link. The keeper provides information about the temperature, weather conditions, names of the incoming/outgoing vessels, maintenance of the lighthouse. The journals record commerce and pleasure crafts passing in and out of the harbor. He notes deaths in the community and even one where Queen Victoria died.

We hope one day to have the National Archives log books digitized and made available, but for now enjoy reading about the daily life of the keepers.

A log book recorded the general station events such as the weather, storms, times keepers left and returned and where they went, even births and deaths were recorded, especially for Port Sanilac. Light keepers either wrote the minimum required or in some cases filled it out more than anyone could have imagined. One light keeper at the Grand Island East Channel Lighthouse wrote short stories in his log book. One story talked about owls landing on the lantern room railing and what the owl did for a while. Another log book from Waugashaunce was found to contain love notes written back and forth between a keepers daughter and one of the assistants possibly although no last names were specifically mentioned it is what can be assumed. One of the entries asks for her hand in marriage. Log books contain a general overall station history and are very insightful into the daily routine of light keeping.

The Log books for the Port Sanilac are found in two places, in the Sanilac District Library which have been transcribed as well as the National Archives with a gap in the log books from December 1905 to December of 1917. If you know where these missing log books are, please contact us.

We have located the last 2 volumes (July 1, 1918 to October 1926) at the National Archives and will have the information digitized and available to the public soon.

The Dwelling

The dwelling was located to the south of the tower, with the two connected by a covered passageway which also housed the single entrance to both structures. The gable end walls of the two story brick dwelling extended vertically above the roof line, and featured a stair-stepped detail at their upper edge which mirrored the stepping of the tower gallery support. Erected atop a full cellar, which served double duty for the storage of both household goods and lamp oil, which was stored in a separate purpose specific room.

Richard W Morris

Richard W Morris, was promoted to the position of Acting Keeper of the new Light after serving four years as the Second Assistant at the Thunder Bay Island Light, and moved into the new dwelling on October 6. He brought his wife, Sarah, and children, Blanche and Bert, along to the new assignment The construction crew completed their work on October 13, and Morris climbed the tower with kerosene fuel in hand to exhibit the light for the first time on the evening of October 20, 1886. With no fog signal, brand new quarters and situated in close proximity to the growing town, Port Sanilac likely seemed an "Sweetheart" assignment to Morris after the rigors of life on Thunder Bay Island, and doubtless Morris and his family quickly settled into a comfortable routine.

To better differentiate the light from the lights of the town behind the tower, the characteristic of the light was changed to fixed red on July 15 1889 through the installation of a ruby-colored glass chimney over the lamp.

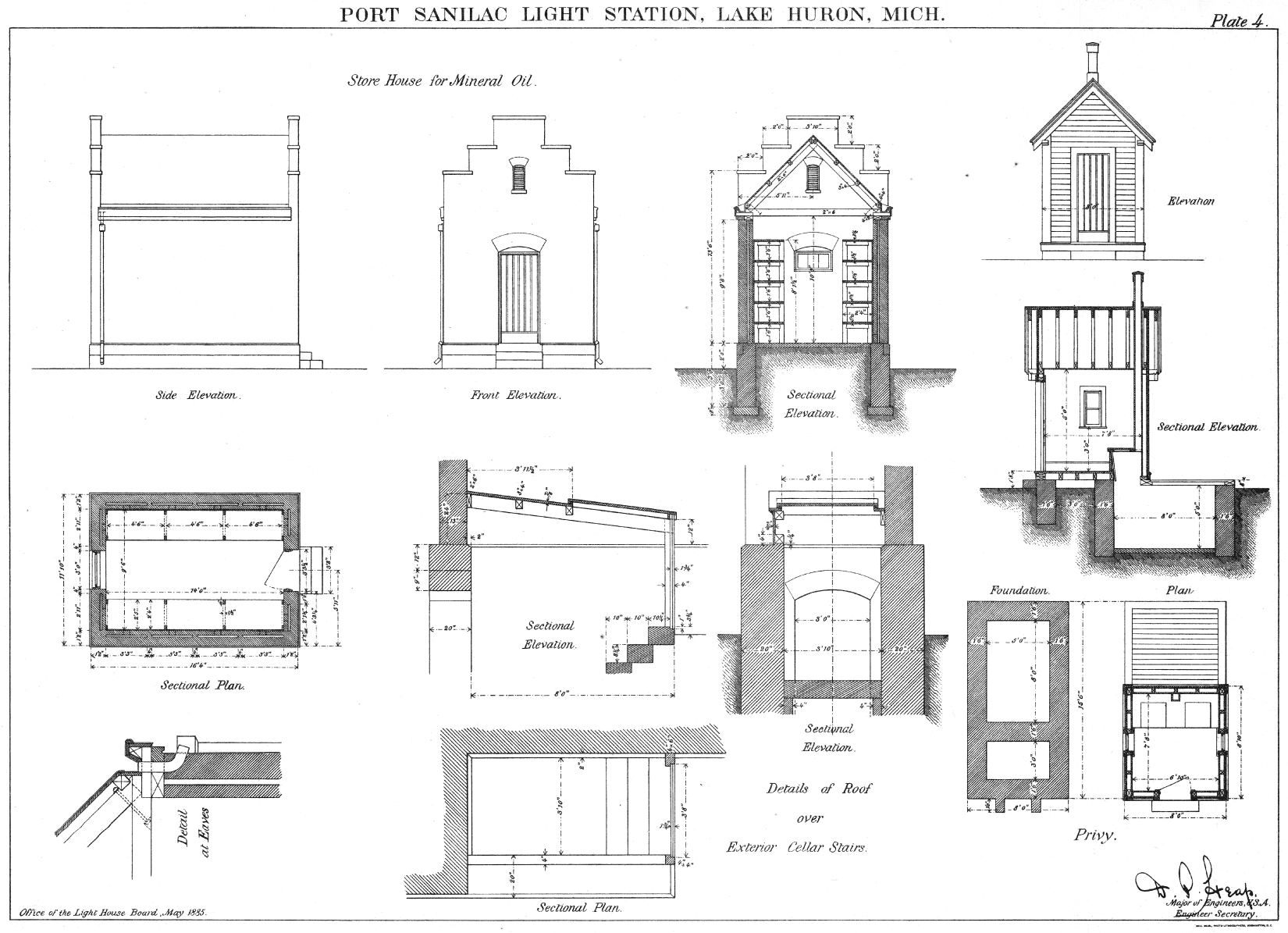

Change to Kerosene

Prior to the 1870's, either sperm whale or colza oil had been used for the lamps in US lighthouses. Minimally flammable, and prone to congealing at lower temperatures, the oil was stored within the dwellings where it would stay warm and its viscosity low. However, with the change to the significantly more volatile kerosene, a number of fires had broken-out at stations around the nation, and the Lighthouse Board embarked on a project of erecting stand-alone oil storage buildings at all of the nation's lighthouses through the 1880's and 90's. To this end, a 360-gallon brick oil storage building was constructed at the station in 1889. Standing 11 feet 10 inches by 16 feet 4 inches in plan. While the Lighthouse Board had two standard plans to which such structures were normally built, they thoughtfully modified the plan to include extended gable end walls with the stair-stepped design to mirror those on the dwelling itself.

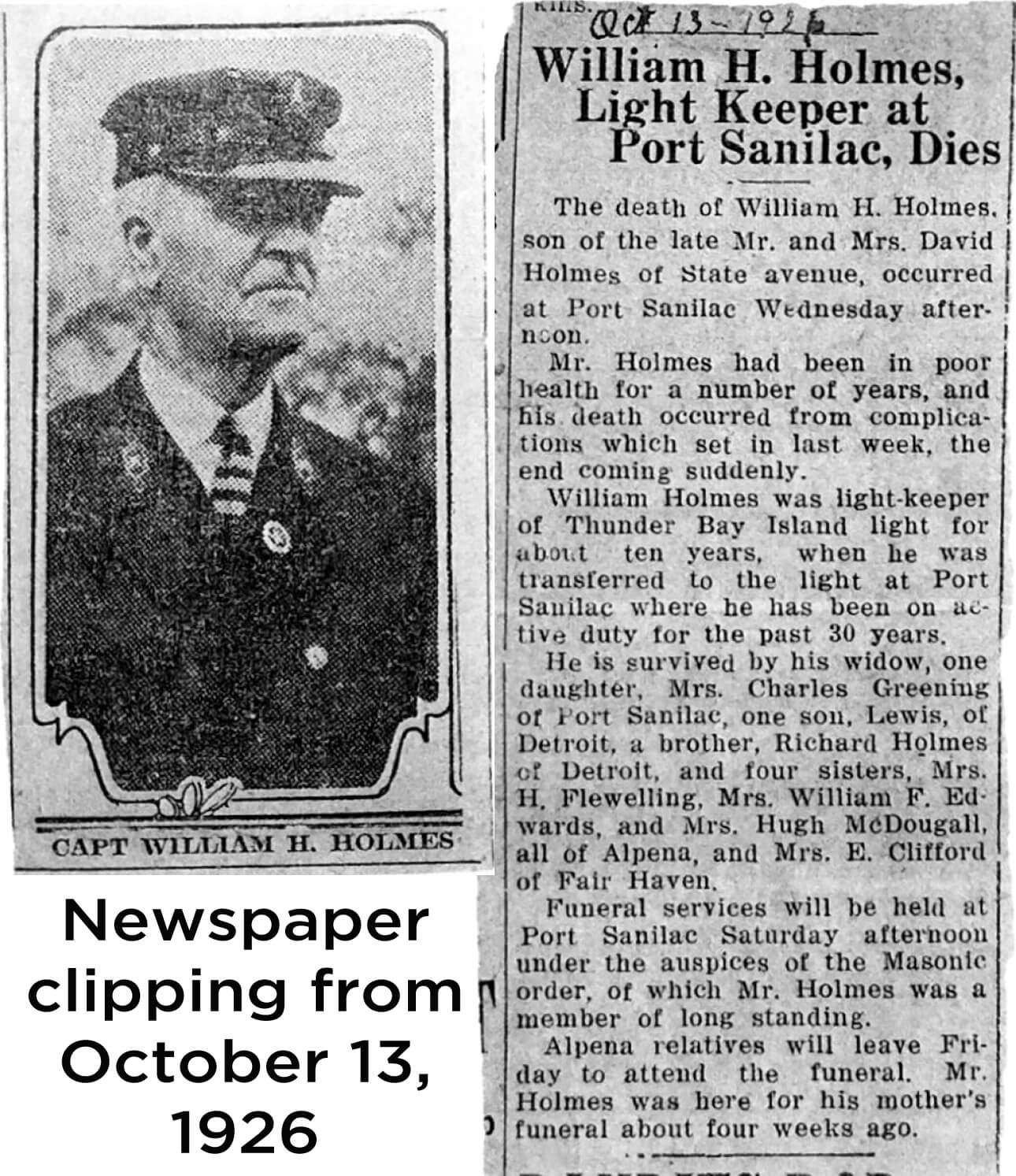

Keeper Morris resigned from lighthouse service on May 1, 1893, and was replaced by William H Holmes, another Thunder Bay Island alumnus, who was promoted to the position after serving almost six years as First Assistant at the island station.

NOTE: The drawings for the light station have the oil house and privy on the same drawing listed as Plate 4 in a series that continues. On the bottom of the drawing lists that it was approved in 1885 along with the other plans for the light station. This information contradicts the note in the file about the oil house being constructed at a later date. More research is needed to verify these conflicting facts and it is something we will continue to research.

Captian Holmes

Holmes, a former employee of the US Life-Saving Service, was married to Capt. Sinclair’s daughter, Grace. Grace’s mother and Keeper Morris’ wife, Sarah, were sisters. The fact is, Morris had generously resigned his position so that his niece and her husband, Grace and Will Holmes, could move to a lighthouse assignment where their children could attend school onshore.

Thunder Bay Island is more than sixteen miles off the Alpena coast. During the school year it would have been impossible to shuttle children back and forth to attend class. The only other option would have been to separate Holmes from his family. Grace and their children would have lived in Alpena and William would have been out on the island for days on end. William’s older sister had just died and he and Grace had taken her infant daughter, Gracie, into their home, so the prospect of separation would have been daunting for the young family, which also included older children, Hattie and Lewis Holmes.

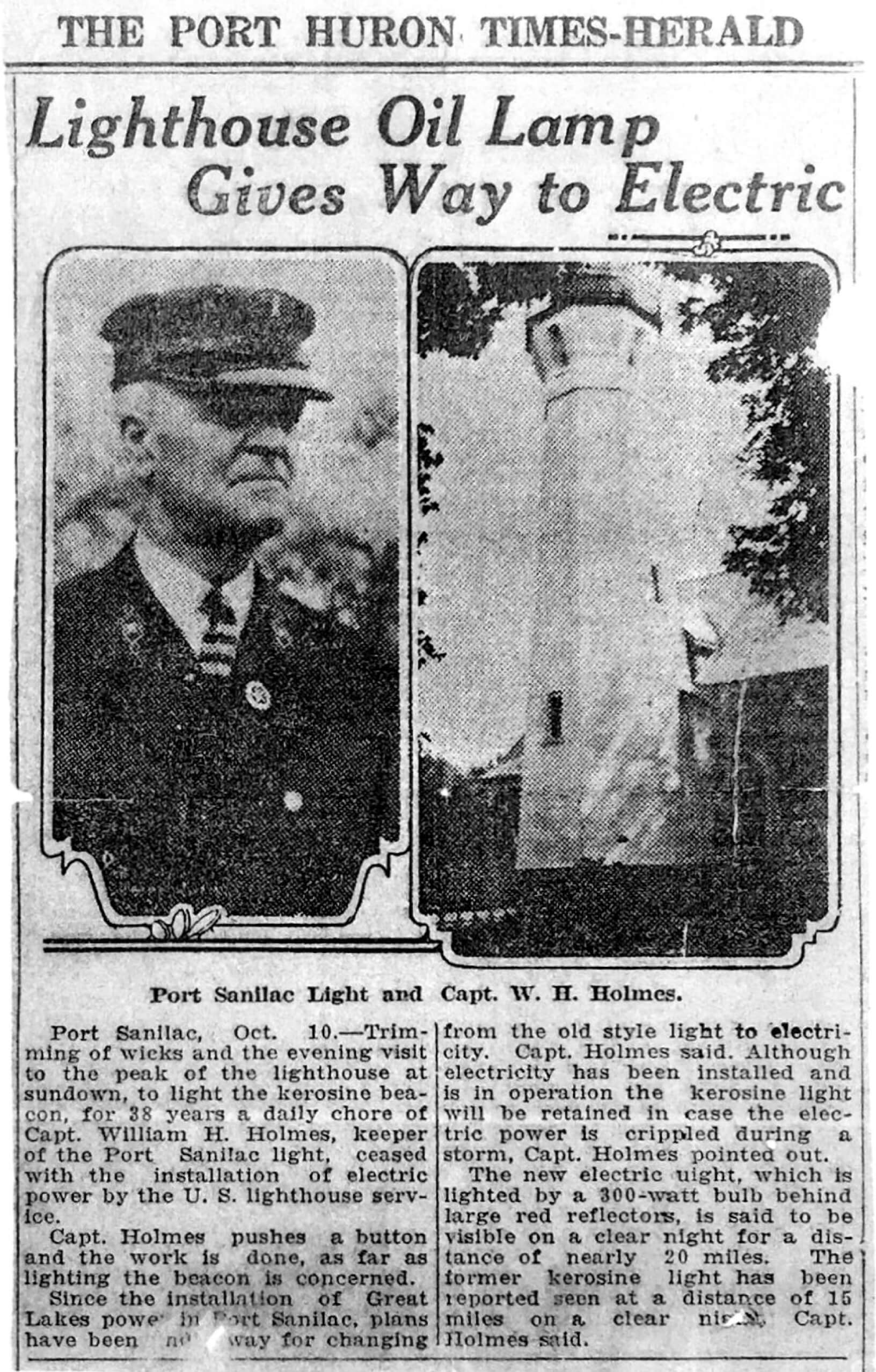

Capt. Holmes and Grace ran the Port Sanilac lighthouse like a tight ship. The Captain battled neuritis for eight years and there were many nights before the electrification of the light in 1924, when Mrs. Holmes lugged the kerosene up the tower steps herself; once at dusk and again at midnight. Her grandfather was a lighthouse keeper, as was her father, and her husband joined the family business after they were married. Grace had lived her entire life in lighthouses and knew as much about operating one as any man.

How Electricity Changed Point Sanilac

With the availability of reliable electric power in the town which was growing up around the Light, the station was electrified in 1924. With electrification, the characteristic of the Light was changed on the opening of the 1925 navigation season through the installation of an 18,000 candlepower incandescent electric lamp and electronic timer and switching mechanism to flashing-white. Thus equipped, the light was set up to exhibit a triple flash every 10 seconds, with a resulting increase in visibility to 16 miles at sea.

William Homes - 1926

With the availability of reliable electric power in the town which was growing up around the Light, the station was electrified in 1924. With electrification, the characteristic of the Light was changed on the opening of the 1925 navigation season through the installation of an 18,000 candlepower incandescent electric lamp and electronic timer and switching mechanism to flashing-white. Thus equipped, the light was set up to exhibit a triple flash every 10 seconds, with a resulting increase in visibility to 16 miles at sea.

Present Day

The dwelling only was sold into private ownership in 1928 to Carl Rosenfield, whose family took over ownership with the government selling them the light tower in 2000. In December of 2015 the lighthouse was sold to the Shook’s who undertook a major restoration of the entire light station.

The 4th Order Fresnel Lens was removed from service September 12, 2016. The light continues to guide shipping on Lake Huron as it has been guiding mariners since it was built. The Coast Guard maintains access to the tower and the LED Beacon that replaced the Fresnel lens in the lantern room. The current LED characteristic is flashing-white every 2.5 seconds.

Help Us tell Port Sanilac's story

We are currently seeking photos of the Port Sanilac Lighthouse Keepers, their families and activities they did while at the light station. If you have any information that will help tell the story of the lighthouse, please contact us. Thank you.